Some aspects of life in Germany changed immediately upon the outbreak of war on 1 September 1939; others changed more slowly. Germany did not fully mobilise at first. In fact, it was not until 1943 that Germany focussed its economy on war production. Nazi policy was not to burden the people on the home front because they feared domestic unrest; something the Nazis believed had led to Germany’s capitulation in 1918. For most Germans, life during the early stages of the war was reasonably comfortable. Germany was blockaded by Britain so there were some shortages, especially of oil, rare metals, and to some foodstuffs. General building materials had been diverted to war purposes and were also hard to get. But thanks to the Nazi-Soviet Pact, large shipments of raw materials were being sent regularly from the Soviet Union. In addition, Germany ruthlessly plundered the countries it occupied. The Nazis seized military hardware, industrial plant, railway stock, manufactured goods, foodstuffs and livestock.

After the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, life in Germany started to deteriorate. The supply of raw materials dried up and there would be a delay before arrangements could be made to plunder the Soviet Union on any meaningful scale. The retreating Soviet forces carried out a ruthless policy of scorched earth, destroying anything useful they could not carry away with them.

Rationing

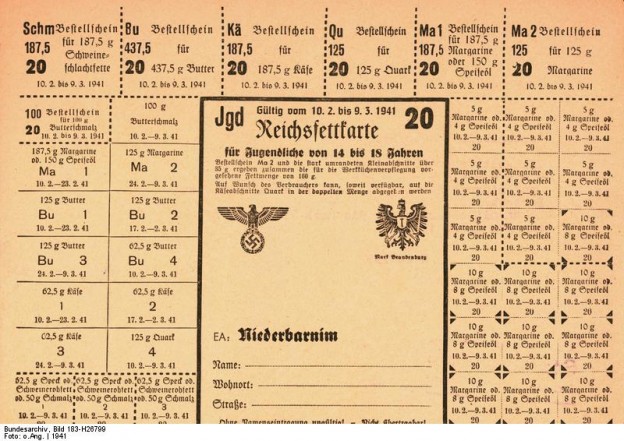

Rationing was introduced to Germany in late August 1939, shortly before the outbreak of war. Initially most foodstuffs were rationed together with clothing, shoes, leather and soap.

Rations were sufficient to live off, but did not permit luxuries. Whipped cream became unknown from 1939 until 1948, as well as chocolates, cakes with rich crèmes etc. Meat could not be eaten every day. Other items were not rationed, but simply became unavailable as they had to be imported from overseas, coffee in particular. Vegetables and local fruit were not rationed, but imported fruits became unavailable. Ration stamps were issued to all civilians. These stamps were colour coded and covered sugar, meat, fruit and nuts, eggs, dairy products, margarine, cooking oil, grains, bread, jams and fruit jellies. Imitation coffee was made from roasted barley, oats, chicory and acorns. Various imitation foods were produced. Cooked rice mashed into patties and fried in mutton fat became ersatz meat. Rice was also mixed with onions and the oil reserved from tinned fish to ersatz fish. Flour for bread was eked out using ground horse-chestnuts, pea meal, potato meal, and barley. Salad spreads were made using chopped herbs mixed with salt and red wine vinegar. Nettles and goat’s rue were used in soups or were cooked and mixed together as spinach substitutes. Ration stamps did not entitle civilians to free hand-outs; items still had to be paid for. Food stamps were also needed to eat in restaurants. The waiter would remove all of the stamps needed to produce the meal in addition to taking payment. Theft of stamps or counterfeiting them was a criminal offence and typically resulted in a spell of detention at a forced labour camp. As the war went on it might mean a death sentence.

As the war began to go against Germany in the Soviet Union and as Allied bombing began to affect domestic production, a more severe rationing program had to be introduced. The system allowed extra rations for men involved in heavy industry, but supplied only starvation rations for Jews and Poles in the areas occupied by Germany. In April 1942 bread, meat and fat rations all were reduced. This was explained to people at the time by poor harvest, lack of manpower for farming, and the increased need to feed the armed forces and the millions of forced labourers and refugees that had come to Germany.

Force Labourers and Refugees

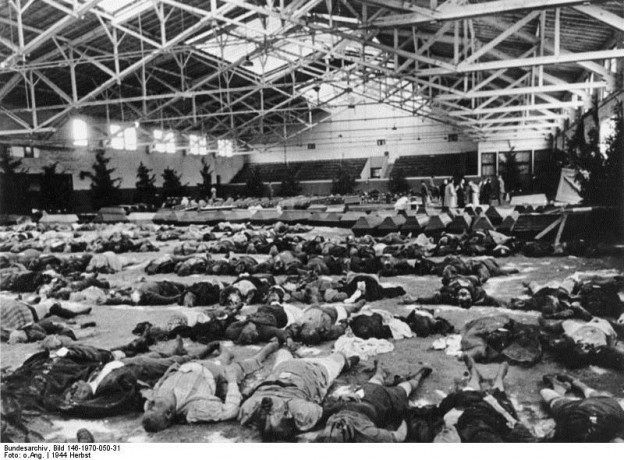

The Nazis forced people from the occupied countries and prisoners of war to work in Germany. Many died from bad living conditions, mistreatment, and malnutrition. More than five million civilian workers and nearly two million prisoners of war were eventually brought to Germany to work in key industries and on the land. Although their rations were minimal, nevertheless they needed to be fed. They also had to be accommodated, usually in large basic barrack huts which required scarce building materials.

During 1944-45, over 2.5 million ethnic Germans fled from Eastern Europe, hoping to reach Germany before being overtaken by the Russians. Although half a million died on the march, the survivors also had to be fed and housed, putting an even greater strain on a Germany that was by then desperately short of resources.

Food Supply and Storage

Many Berliners grew herbs and vegetables in their gardens or on allotments. Rabbits were also raised and could be kept in apartments. They were known as balcony pigs. In many families, caring for the rabbits became the responsibility of the children.

Soldiers in newly occupied areas often sent their families suitcases and even crates filled with fresh eggs, cheese, and chocolate. There was a thriving barter business and people would often travel into the countryside to swap goods for fresh food supplies. Those lucky enough to have friends or family in the countryside found it easier to cope.

Although refrigerators had been invented, they were rare, even in shops. A typical grocer who had meat would have had a display case kept cool with blocks of ice. Fresh produce would have been available during the late spring, summer, and early fall. It was not rationed but was subject to availability.

Some of the larger employers, particularly armament plants, had canteens for the convenience of their employees. Even then, food quality and selection was very limited.

The Black Market

Shortages resulted in a thriving black market. Nearly anything was available on the black market for a price or barter. There was massive inflation in food prices by the end of the war. Officially, selling and buying goods on the black market might result in a death sentence but there was widespread corruption and Nazi officials often turned a blind eye in return for bribes in cash or goods.

Fuel For Heating and Cooking

A large number of urban homes were heated with steam radiators that required coal to fuel the boilers. Many kitchens had cast iron stoves and also were fuelled with coal, or with wood. Parks, such as the extensive Tiergarten in Berlin, were stripped of trees for use as fuel for heating and cooking. All over Germany, Hitler Youth and members of the labour service harvested potato stalks to ship to a plant in Weimar where they were turned into fuel pellets.

Gas stoves and oven were also commonly available. Although electric stoves existed as early as 1890, they were rare. In any case electric power became more erratic as bombing took effect later in the war. At the end, power supplies failed completely in Berlin, the wood had run out and supplies of coal ceased.

Attacked at Home

In the early stages of the war, Britain’s RAF had little ability to strike targets effectively in Germany. Almost all targets were on the coast and there were relatively small numbers of bombing aircraft available. Disruption to German life was slight, except that the black-out, the switching off of all lights at night to make it harder for enemy aircraft to find their way to their targets, caused considerable inconvenience. At first, more casualties were caused by accidents in the dark than by bombing. Crime rates also increased under the cover of darkness.

Berliners read official guidelines and instructions in case of air attack.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J07186 / CC-BY-SA

As the war wore on, however, more and better aircraft became available to the Allies and attacks become heavier. After the United States of America entered the war in December 1941, its aircraft too began to attack Germany.

Especially for those Germans living in the industrial areas of the Rhineland and the Ruhr and close to the North Sea and Baltic coasts, the RAF became a frequent visitor by night and the US Airforce by day. In May 1942 the first massed air raids deliberately targeting residential areas took place against Germany at Lübeck. In June 1943 Essen and Cologne saw the first ever 1,000 bomber raids. From then on, large scale bombing of the cities became a regular occurrence. Estimates of those killed in Germany by allied bombing vary between 350 000 and 420 000. Many, many more were serious injured and millions made homeless.

Berlin had been bombed as early as August 1940, but distance from Britain and lack of suitable aircraft meant that raids on Hitler’s capital city were very limited. Later, as more aircraft became available, newer types introduced, and bases seized closer to Germany, the pace and scale of attacks increased. A major bombing offensive was conducted against Berlin between November 1943 and April 1944, when aircraft were switched to support the D-Day landings in Normandy. Raids in November 1943 alone made 400 000 Berliners homeless. After the lull occasioned by D-Day, the allies resumed their heavy bombing of Germany in the autumn of 1944, and Berlin continued to be attacked until it fell to the Red Army in April 1945.

Bombing eventually had a major disruptive effect on the German population. Aside from the casualties and physical damage caused, loss of sleep and interruption to water and power supplies caused considerable inconvenience and fatigue. Nevertheless bombing tended to stiffen resolve and draw people together, whether they supported Hitler or not.

Evacuation, initially of children but later of women and the elderly, was organised and proved very unpopular, at least in the early stages. Later as the cities were attacked severely, people wanted to get themselves or their loved ones away from the danger areas. However, catering adequately for the millions of homeless and displaced persons proved impossible. Conditions for evacuees often were poor and many chose to return to the cities despite the dangers and hardships.

Hearts and Minds

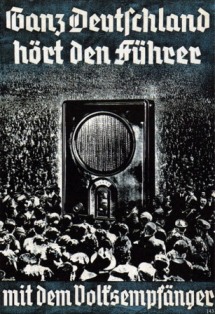

Manipulation of public opinion was given a very high priority in Nazi Germany. The Party took early control of the press and radio through The Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Cinemas and the theatres also came under the direction of the Ministry. Strict laws were passed to control the media and extensive censorship was put in place. Considerable resources were allocated to propaganda. A very cheap radio set, the People’s Receiver, was made available to enable the populace to tune in to official channels.

There were strict penalties for listening to foreign broadcasts during the war. Nevertheless, especially as the war wore on, many people risked imprisonment, and even sometimes death, to tune in to broadcasts from outside Germany. The BBC was especially popular.

The Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda funded theatre performances and the making of films, which increased considerably their control over what was performed and screened. Some productions were overtly propagandist but it soon became clear that it was better to provide cheering light-entertainment through all media channels.

Before the war, the Nazis had become very proficient at staging mass events, such as rallies and pageants at which Hitler often spoke to great effect. Although this was not possible during wartime, Hitler continued to be seen on film, heard through the radio and attend smaller gatherings. However, by 1943, confidence in Hitler began to slip as the war turned against Germany and he failed to deliver his promises. He became more and more reclusive and his last radio broadcast was on 30 January 1945. His last public appearance was on 20 April 1945, his 56th birthday, when he presented Iron Cross medals to Hitler Youth boys in the garden of his Chancellery.

By the last months of the war, people had become very cynical about official news, especially in Berlin which had always been the most anti-Nazi area of Germany. Public opinion was by then more influenced by rumour and unofficial news.