The Battle for Berlin

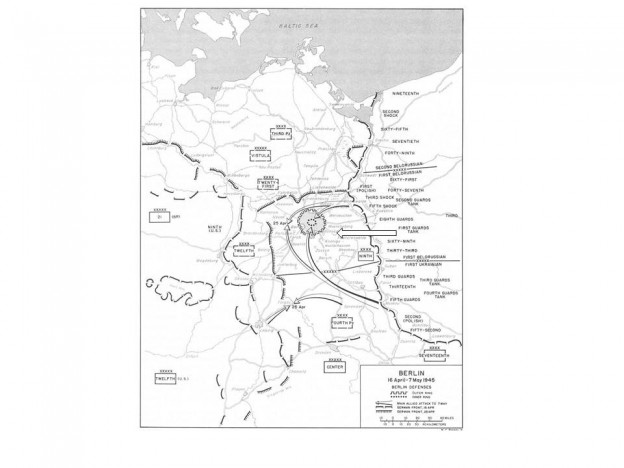

The Soviet assault on Berlin was the final great battle in Europe during World War Two. It was fought between 16 April 1945, and 2 May 1945. It was one of the bloodiest battles of the war; approximately 350,000 attackers and 480 000 defenders were killed. When it was over the city lay in ruins and did not recover for decades.

The direct assault began in the early hours of 16 April. Nearly one million soldiers of the Red Army and more than 20,000 tanks and artillery pieces attacked 100,000 German soldiers and 1,000 tanks and guns defending a low ridge 40 miles to the east of Berlin called the Seelow Heights. In addition Soviet and Polish Communist forces attacked to the North and South.

On 19 April after savage fighting with heavy losses, the Red Army broke through and nothing but broken German formations lay between them and the direct route into Berlin. The Soviet forces also advanced to surround and isolate the city to the north and south. On 20 April, Adolf Hitler’s birthday, Soviet artillery shelled the centre of Berlin. The artillery bombardment did not stop until the city surrendered.

The Red Army began advancing into the city proper on 23 April and by 25 April had reached the inner zones, the same day as encircling Soviet forces linked up with armies of the United States, Britain and France to the west and south-west of Berlin. The city’s defenders formally surrendered on 2 May after attackers, defenders and civilians had suffered very heavy casualties. The city centre especially was badly damaged. Some chaotic fighting continued to the north-west, west and south-west of Berlin until 8 May as German units tried to break through the Soviet lines to give themselves up to the western allies.

Forces and Tactics

German forces consisted of depleted, badly equipped and disorganized Army and SS formations, as well as many elderly Volkssturm (militia), teenagers of the Hitler Youth, policemen, firemen and air force personnel. Any male of any age capable of firing a weapon was conscripted into the final battle for Berlin.

Although there were areas of narrow streets, especially in the suburbs, much of the centre of the city consisted of apartment blocks lining wide straight roads. There were scattered parks, industrial estates and large railway marshaling yards. The topography is predominantly flat with some low hills. The apartment blocks, built in the second half of the 19th century, were four and five stories high, solidly built built around courtyards reached from the street through passages wide enough to take a horse and cart or a small truck. Many of the courtyards were linked to each other through more passages, forming a network of courtyards surrounded by high buildings.

Larger apartments usually faced the street and smaller ones faced the inner courtyards. Berlin was broken up by rivers and canals with many bridges, most of which were narrow. Barricades had been erected in the city centre using rubble from earlier allied bombing, commandeered building materials, and large vehicles such as trams. In some places the trees lining the streets had been partially cut through to make it easier to drop them as obstacles when the time came.

However, systematic arrangements to erect defences were not put in place until Adolf Hitler’s birthday on 20 April.

A roadblock at the S-Bahn station Hermannplatz in Neukölln is reinforced by Volkssturm with material from bombed-out houses. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J31387 / CC-BY-SA

The barricades that were erected were often not defended or were abandoned after token resistance. At some, however, the defenders put up a determined resistance causing delay and inflicting casualties on the attackers. The teenagers of the Hitler Youth could be the most fanatical. SS units tended to avoid defending barricades because they could be raked easily by direct fire. Instead, they put snipers and machine guns on the upper floors and roofs of buildings above the level that tanks could elevate their guns. These defenders were armed with petrol bombs and explosive charges as well as rifles and machine guns. SS troopers armed with panzerfaust light anti-tank rocket launchers often occupied cellars. These tactics were copied by the Hitler Youth and the veterans amongst the Volkssturm as soon as it became clear how effective they were, and how vulnerable the barricades were to Red Army firepower.

The Red Army had learned a lot during four years of war, much of which  centred on major city battles such as at Stalingrad, Leningrad, Königsberg and Breslau. Although many units had large turnovers, most retained a core of very experienced veterans. The equipment shortages of the first years of the war had been overcome and ammunition was plentiful. They organised their attacks around company-sized units of eighty to a hundred men, broken into platoon assault groups based on sections of six to eight carrying a mix of weapons. Engineers were attached to clear particularly difficult obstacles. Sub-machine guns, flamethrowers and grenades were all employed to great effect.

centred on major city battles such as at Stalingrad, Leningrad, Königsberg and Breslau. Although many units had large turnovers, most retained a core of very experienced veterans. The equipment shortages of the first years of the war had been overcome and ammunition was plentiful. They organised their attacks around company-sized units of eighty to a hundred men, broken into platoon assault groups based on sections of six to eight carrying a mix of weapons. Engineers were attached to clear particularly difficult obstacles. Sub-machine guns, flamethrowers and grenades were all employed to great effect.

These assault groups were closely supported by tanks, field artillery whenever possible, firing directly at any defended locations. Often troops armed with sub-machine guns rode on the vehicles, spraying doorways and windows with suppressive fire. Anti-aircraft guns were also sometimes used to provide direct fire support.

After the first few days, the Red Army changed tactics. Troops moved from house to house instead of attacking directly down the streets. They blasted through the walls of adjacent buildings using explosive charges and captured German panzerfausts, and infiltrated across roof-tops and through attics. Holes previously had been knocked through many of the walls between cellars to make it easier for people sheltering in them from bombing raids to move around and to escape. Now Soviet soldiers made use of them.

After the first few days, the Red Army changed tactics. Troops moved from house to house instead of attacking directly down the streets. They blasted through the walls of adjacent buildings using explosive charges and captured German panzerfausts, and infiltrated across roof-tops and through attics. Holes previously had been knocked through many of the walls between cellars to make it easier for people sheltering in them from bombing raids to move around and to escape. Now Soviet soldiers made use of them.

The Civilian Population

The civilian population of Berlin had not been evacuated and many were killed or wounded during the fighting. It is estimated that over two million civilians were trapped inside Berlin when the Red Army completed its encirclement of the city. Organised government effectively ceased on 20 April when Hitler ordered the evacuation of important ministries and officials. Water and power supplies, which had been uncertain for some time, began to fail completely during the last two weeks of the battle. Civilians huddling in cellars or waiting in their apartments burned anything they could in their stoves to keep warm and to heat what little food remained. Coal supplies ceased to be delivered. Although food rations were in theory still issued, in practice they were very uncertain. The civilian population ate whatever came to hand, including some of the animals in the Berlin Zoo and the corpses of dead cart horses lying in the streets.

If a street surrendered immediately to the Soviet attackers, hanging out white cloths and offering no resistance, usually it came to little harm. However, SS units particularly would take revenge on these perceived ‘traitors’, and if they re-occupied the area, as they often did in the very fluid fighting, they would shoot or hang men as examples. If resistance was offered to the Red Army then little mercy was shown. Buildings were blasted into rubble by tanks and artillery, burned out with flamethrowers or saturated with small arms fire and then explosives and grenades were thrown in. Usually any male still alive after that would be shot out of hand by the attackers. Rape was rare at this stage. It only became widespread towards the end of the fighting, especially when second-echelon Red Army units, notorious for ill-discipline, moved into the city. Figures for civilian casualties sustained during the fighting are uncertain but most estimates suggest that 125 000 or more were killed and many, many more wounded. Perhaps 100 000 or more suffered rape during the latter stages of the fighting and during the immediate period of occupation that followed until order was restored.

More

For more about the Battle for Berlin in 1945, the following are recommended:

Books

- A Woman in Berlin, (anonymous), Virago Press, 2007.

- Berlin Dance of Death, Helmut Altner, Spelmount Ltd, 2005.

- Berlin At War, Roger Moorhouse, The Bodley Head, Random House, 2010.

- Berlin 1945 – End of the thousand year Reich, Peter Antill and Peter Dennis, Osprey Publishing, 2005.

- The Fall of Berlin 1945, Anthony Beevor, Penguin Books 2003.

- The Fall of Berlin, Anthony Read and David Fisher, W W Norton and Company, 1992.

Films

- Downfall, Director Oliver Hirschbeigel, Screenplay: Bernd Eichinger, Constantin Film 2004.

- I Was Nineteen, Director Konrad Wolf, Screenplay: Konrad Wolf and Konrad Kohlhaase, DEFA 1968.

- The Downfall of Berlin, Director Max Färberböck, Screenplay by Max Färberböck, Constantin Film 2008.